Improving ourselves to death (or why you should stop reading self-help books)

On living in a self-improvement culture, secular monks, utilitarian pragmatism, and the novel in the workplace

The bones of the following essay come from a piece I wrote a few years back, which was originally published on my blog and Mockingbird. I’ve decided to expand the ideas of the original article a bit, as it pertains to a number of topics I’m supremely interested in. Namely, how the arts can point us towards the kind of flourishing we were made for.

Part I (today’s essay) will focus on the ills of self-improvement culture and the unique value art brings to our vocations. In the next essay, Part II will explore the deeper importance of art to our lives and souls.

But first, allow me a short prelude to share the genesis of this essay.

Six years ago, I was working in an office job at a great company. My colleagues were sharp, kind, thoughtful, creative, and virtually all of them were go-getters. The company itself placed a high value on cultivating a learner’s mindset.

Case in point: Every year they would gift us a book (typically related to business, leadership, productivity, customer service, etc.), and it was very common for teams to read a book together as part of their professional development. In fact, when I was first hired, the company would hand new employees a stack of books. (A delightful gift for a book nerd like me!)

But at some point during my tenure, I started noticing a puzzling trend. In conversation after conversation with my colleagues, I heard the same refrain again and again:

“I can’t remember the last time I read any fiction.”

To be crystal clear: This isn’t a hit piece on that company or my former colleagues—I think this kind of statement is quite common in many business settings.

But for this literature nerd with some mildly contrarian instincts, dear reader, it was a bridge too far. It bugged me to no end. It seemed that an implicit question lay at the heart of the issue:

“Why would I waste my time on a novel when I could read the latest business/leadership/self-help book and learn something practical that will ACTUALLY benefit me?”

This is a question I have thought about quite a bit. And I believe it represents a much broader, deeper cultural issue writ large.

This was the central question I set out to answer in my original essay.

I hope it gently persuades a few of you to pick up a collection of poems or a Charles Dickens novel.

In 2018, Alexandra Schwartz wrote a piece in The New Yorker called Improving Ourselves to Death in which she thoroughly outlines the negative consequences of living in a “self-improvement culture.”

At one point, Schwartz quotes a line from British journalist Will Storr, author of Selfie: How We Became So Self-Obsessed and What It’s Doing to Us.

“We’re living in an age of perfectionism, and perfection is the idea that kills. People are suffering and dying under the torture of the fantasy self they’re failing to become.”

Storr’s words hit me like a freight train. They perfectly crystallized a personal struggle I hadn’t yet put into words: living and “suffering under the torture of the fantasy self I’m failing to become.”

For years, I had been haunted by an ideal of myself that I slowly realized would never come to fruition. This “Mega Mark” got up every day at 5 a.m. for an hour-long workout, followed by an hour-long devotional, followed by an hour-long passion project work session, followed by hours of passion-filled, excellent-beyond-belief work, followed by a fun, romantic evening with my wife that’s laced with intentional conversations, followed by an hour-long reading session, followed by 8-9 hours of perfectly restful sleep.

As anyone could guess, my days rarely look like that. (Especially now that I have three young kiddos!) But for years I lived in the tall shadow of this “Mega Mark” and felt a twinge of guilt almost daily for not being more like him.

Don’t get me wrong—striving to grow in every area of life (professionally, relationally, spiritually, etc.) is a good and noble thing. And I am by no means advocating for removing all discipline from our lives. I believe cultivating life-giving habits is essential to our flourishing.

But Schwartz’s article shines a light on a glaring blindspot in our culture and personal lives. It’s far too easy to get carried away—to become so focused on self-improvement that we’re plagued by the guilt of never measuring up to our own standards.

When this becomes the norm, we lose several things critical to our humanity, not least of which is our ability to rest. (How can you, when you’re always wondering, “Could I be doing more?”) Not only that, we also lose our ability to work from a place of rest. Instead, we become anxious, fear-filled doers—racked with guilt and depression when we fail to live up to our own ideals.

Which is one of the many reasons why we need the arts.

If you have any doubts about our culture’s bent towards self-improvement, look no further than the best-sellers shelf at the bookstore. Popular titles like Tim Ferriss’ Tools of Titans: The Tactics, Routines, and Habits of Billionaires, Icons, and World-Class Performers or Charles Duhigg’s Smarter, Better, Faster promise that if we would only read their books, the secrets to doing more, achieving more, and becoming more will be ours.

I’m not dogging on books like these—I have read and benefited from a number of them. I’m sure you have to. But these types of books can breed in us an unhealthy obsession with personal growth.

Ferriss himself is a kind of high priest among a growing group of young men who are so obsessed with optimization that Andrew Taggert called them “secular monks.”

Perhaps you’ve heard of them: They’re into cold showers, intermittent fasting, data-driven health tracking, and meditation boot camps.

In the article for First Things, Taggert describes their worldview:

“As human agents, we should divide our actions into means and ends, and if we’re good optimizers, we will discover and use the most effective means by which we can satisfy those ends. This defines human existence as Ferriss sees it: an endless game of self-one-upsmanship.”

Maybe you haven’t gone full secular monk. But haven’t we all gone through seasons of relentlessly seeking to “optimize” our lives? Again, there’s nothing wrong with trying to cultivate some healthy habits. But can we honestly say that this kind of obsessive “optimization” is the ultimate end for which we were made?

Related to this, several years ago I started noticing an interesting trend. In conversation after conversation, I heard the same line:

“I can’t remember the last time I read any fiction.”

This statement bewildered me to no end. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Eventually, it dawned on me: In a self-improvement culture, there is no room for art. There is room only for things which have an explicit, utilitarian purpose. Literature, art, poetry, films—these have no practical value in and of themselves. So why read a novel when you can learn ten principles from a self-help book?

In the introduction to his book Culture Care: Reconnecting with Beauty for Our Common Life, artist Makoto Fujimura states it plainly:

“The assumption behind utilitarian pragmatism is that human endeavors are only deemed worthwhile if they are useful to the whole, whether that be a company, family or community. In such a world, those who are disabled, those who are oppressed, or those who are without voice are seen as “useless” and disposable. We have a disposable culture that has made usefulness the sole measure of value. This metric declares that the arts are useless. No—the reverse is true. The arts are completely indispensable precisely because they are useless in the utilitarian sense.”

We are living in the Age of the Machine, and one of the driving forces behind it is the kind of utilitarian pragmatism that Fujimura speaks of. If something isn’t deemed “useful” to the bottom line, it is discarded.

When it comes to fiction (and the arts in general), I think many of us take this view: What’s the point? At least nonfiction books teach you practical principles you can actually use.

In the next essay, I will explore and expand upon art’s profound impact on our lives—about how its “uselessness” makes it utterly indispensable to our souls. For now, I want to simply address the misguided notion that art has nothing of value to add to our work.

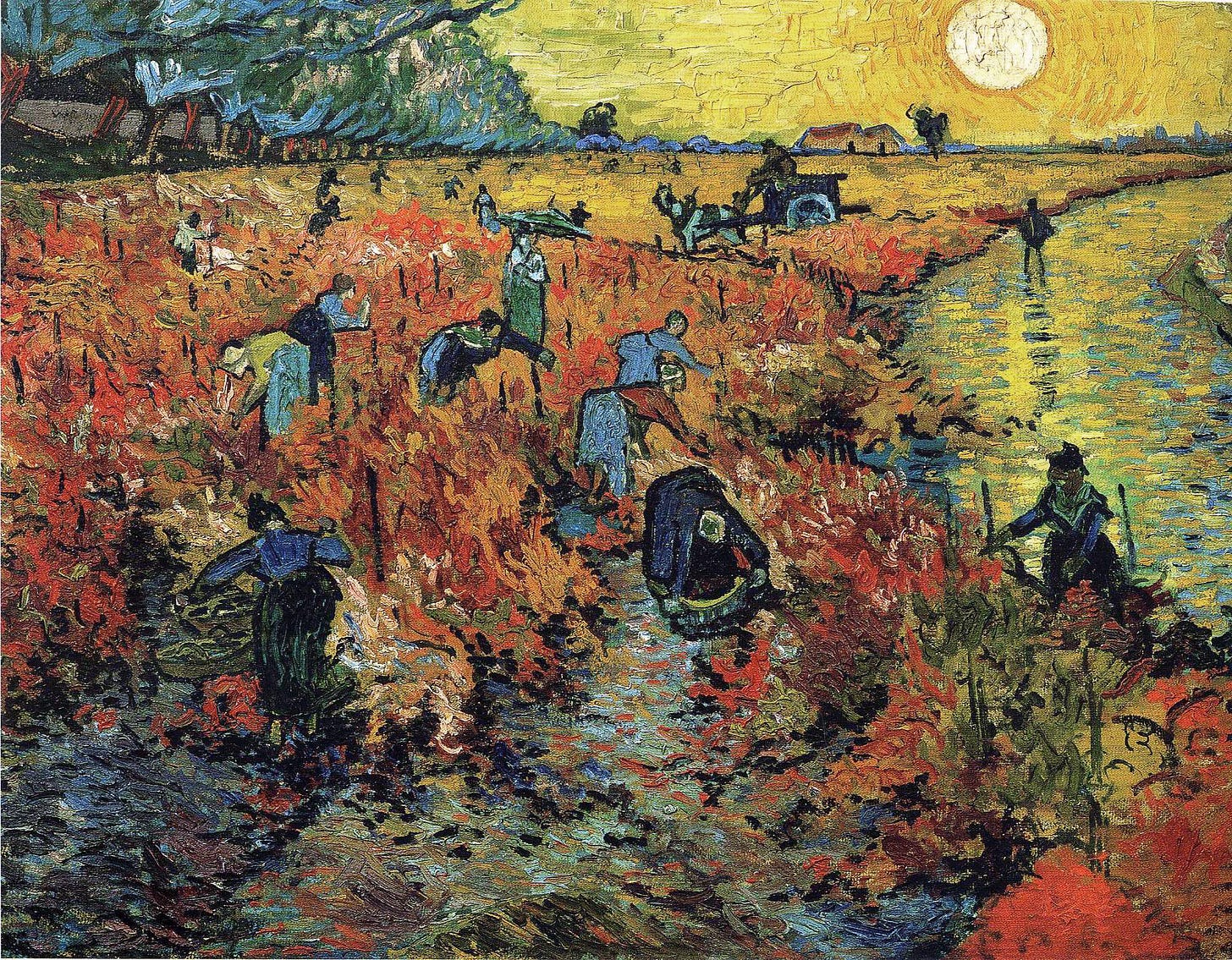

Interestingly enough, many have discovered this simple yet profound truth: art deeply enriches and enlivens our vocations.

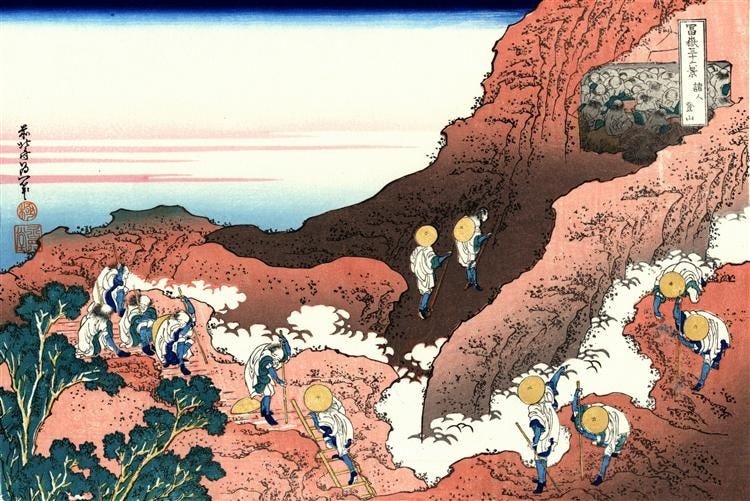

The Catholic writer Henri Nouwen famously spent over four hours observing and studying one of Rembrandt’s paintings, eventually chronicling his experience in a book. But Nouwen isn’t alone. Some of the greatest leaders in history have been avid consumers of art. John Coleman illustrates this point vividly in an article he published in the Harvard Business Review:

“According to The New York Times, Steve Jobs had an ‘inexhaustible interest’ in William Blake; Nike founder Phil Knight so reveres his library that in it you have to take off your shoes and bow; and Harman Industries founder Sidney Harman called poets ‘the original systems thinkers,’ quoting freely from Shakespeare and Tennyson.

In Passion & Purpose, David Gergen notes that Carlyle Group founder David Rubenstein reads dozens of books each week. And history is littered not only with great leaders who were avid readers and writers (remember, Winston Churchill won his Nobel prize in Literature, not Peace), but with business leaders who believed that deep, broad reading cultivated in them the knowledge, habits, and talents to improve their organizations.”

Speaking of Harvard Business School, did you know that HBS offers an elective course called “The Moral Leader” which teaches students leadership through novels like Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro? (An excellent book, by the way.)

In an interview called Read Fiction and Be a Better Leader, professor Joseph Badaracco (who teaches the course) explains why HBS uses works of fiction to teach leadership:

“My view of what makes literature so valuable in the classroom is that it helps students really get inside individuals who are making decisions. It helps them see things as these people in the stories actually see them. And that’s because the inner life of the characters is imagined and described, in many cases, by brilliant writers whose sense of how people really think and how they really work have been tested by time over decades or even centuries.”

Later on, Badaracco discusses why the nuances of fiction are in many cases superior to the general platitudes of most business books:

“But what is troubling [about most management literature] is when you find something, it takes a situation that’s complex and says, well, gee, just do this and this. And this is something that you could kind of explain to an intelligent 12-year-old, and they’d get it. And you just have a sense that no, there’s many more levels of complexity here that are being ignored.

And it is often these psychological, emotional levels of complexity. In an organization, you’re just dealing with other people all the time. And it’s very hard to capture the nuances, the subtleties, the histories, and all the rest of that in a nonfiction book. So that’s why you turn to literature—to get the depth, and the richness, and the realism.”

Perhaps the most precious gift fiction (and art in general) can give us in relation to our work is perspective. In a culture that idolizes performance, improvement, and success, it is far too easy for our work to become our identity. When work is an idol—our biggest source of meaning, purpose, and value—we’re either crushed or consumed by it.

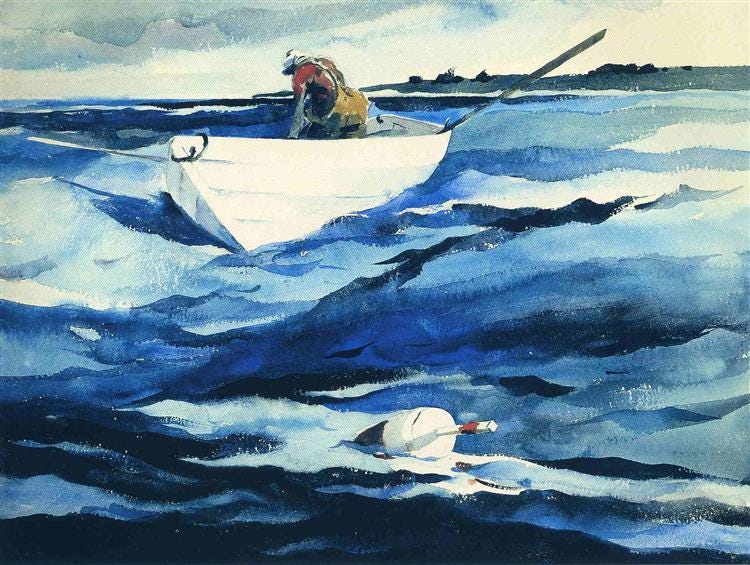

But great art—whether it be a novel, a poem, a painting, a film, or a performance—lifts us out of ourselves. It has the power to crack open what for many of us can feel like a narrow, myopic existence and lead us out into grand new worlds. It can remind us that we are more than just the product of our work and we are living in a story much bigger than ourselves.

For the Christian, art can go even further—a great novel can remind us that we are made in the image of our Creator and our identity is rooted in His work, not ours. Which is exceptionally good news.

And when work is no longer our everything, we’re free to rest, to play, and to dream. And then, we can wake up, roll up, our sleeves, and get to work.

If you found this post interesting or encouraging in any way, please show your appreciation with a comment, like, restack, or share. It helps spread the word to more people!

What do you think? Have you ever experienced the ills of self-improvement culture? Have you ever consciously or unconciously avoided fiction in favor of more practical reads? How have the arts influenced your work in a positive way? Let me know in the comments below!

Beautifully said! I've also found a pattern to many self-help books, in that they all start to feel the same. A constant repetition of one idea, extended to fill the pages of an entire book. Ironically, the "uselessness" of great art provides so much more value than empty, repetitive self-help mantras.

I love this, Mark! In my arts administration degree, I’ve had many realizations about the importance of the arts in society - in business and beyond.

It’s one reason why I adore The Hunger Games trilogy. Suzanne Collins does an excellent job tracing the theme of music and art as a weapon in a society that dehumanized the working class, reducing their worth to their district’s economic output. If you’re looking for some fiction that further these ideas you’ve mentioned, I think you’d really love reading or revisiting those books - especially her newest one, The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes (I think her novels are just as important as Fahrenheit 451 and 1984).

I’m also fascinated also by the connection of arts to democracy on a larger scale too. Unique perspectives, not just the one size fits all maximum efficiency solutions you mentioned, are what fuel a healthy, robust, and productive society. Exposure to ideas is essential to self-actualization. Knowing your voice, understanding how to use it, and identifying the areas in which it is most needed are of the utmost importance.

I loved this post so much and could talk about it for DAYS.