I’m not exactly sure how it happened, but it did.

Poetry happened to me.

It is difficult to put into words, but over the past few years, poetry has become vital to my life. I hope one day to write an essay on exactly how this took shape, but for now I wanted to write a series of essays about three poems that have meant a great deal to me.

Perhaps a glimpse of these three jewels will encourage you to go on your own poetic odyssey.

As kingfishers catch fire

by Gerard Manley Hopkins

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame;

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell's

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.I say móre: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: thát keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God's eye what in God's eye he is —

Chríst — for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men's faces.

“Gerard Manley Hopkins died in 1889 and rose again as a living poet in 1918.”

So begins W.H. Gardner’s introduction to Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins (Third Edition).

Hopkins was a singular figure in the history of English poetry. His mature work consists of only forty-nine poems—none of which were published in his lifetime.

And yet, according to the poet Dana Gioia:

“No other poet has achieved such major impact with so small a body of writing…Hopkins occupies a disproportionally large and influential place in literary history. Invisible in his own lifetime, he now stands as a major poetic innovator who, like Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, prefigured the Modernist revolution. A Victorian by chronology, Hopkins belongs by sensibility to the twentieth century–an impression strengthened by the odd fact that his poetry was not published until 1918, twenty-nine years after his death. This posthumous legacy changed the course of modern poetry by influencing some of the leading poets, including W. H. Auden, Dylan Thomas, Robert Lowell, John Berryman, Geoffrey Hill, and Seamus Heaney.

…Hopkins is one of the great Christian poets of the modern era.”

Hopkins’ story bears a faint resemblance to that of another prodigiously talented if not troubled artist: Vincent Van Gogh.

The poet, like the artist, was completely unknown in his lifetime. Only a handful of people ever read Hopkins’ poetry while he was alive, and most of them (friends, mind) neither liked it nor understood it. By all accounts, Hopkins (also not unlike Van Gogh) was a bit of an odd bird. He suffered from bouts of despair and religious scrupulosity. Hopkins, like Van Gogh, died young—of typhoid fever in 1889 at the age of 44.

And yet, both the poet and the artist created work that shimmers with numinous beauty.

Hopkins, the eldest of nine children, was born at Stratford, Essex, on July 28, 1844. In his 20s while studying at Oxford, he converted to Catholicism and later became a Jesuit priest. Ironically, Hopkins saw his poetic gift and faith to be in conflict with one another. In fact, for seven years, he swore off writing verse altogether.

Then, in December of 1875, a ship called the SS Deutschland crashed off the coast of Britain, drowning many passengers, including five Franciscan nuns. At the request of one of his superiors, Hopkins wrote “The Wreck of the Deutschland,” his first poem in years.

After that, the floodgates of his poetic gift were opened, as it were. The singular feature of Hopkins’ poetry, aside from his signature Sprung Rhythm, is his ability to vividly express what the poet-priest George Herbert called “heaven in ordinarie.”

Hopkins believed, as he wrote in one of his most well-known poems, that

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

This sense of the divine hidden within the everyday is a theme that reverberates throughout his poetry and was deeply informed by his Christian vision of the world.

In the forward to Margaret R. Ellsberg’s The Gospel in Gerard Manley Hopkins, Dana Gioa writes:

“Hopkins’s poetic formation, [Ellsberg] contends, was inextricable from his priestly formation. It was no coincidence that the great explosion of his literary talent occurred as he approached ordination. His conversion had initiated an intellectual and imaginative transformation—initially invisible in the secret realms of his inner life—that produced a new poet embodied in the new priest.

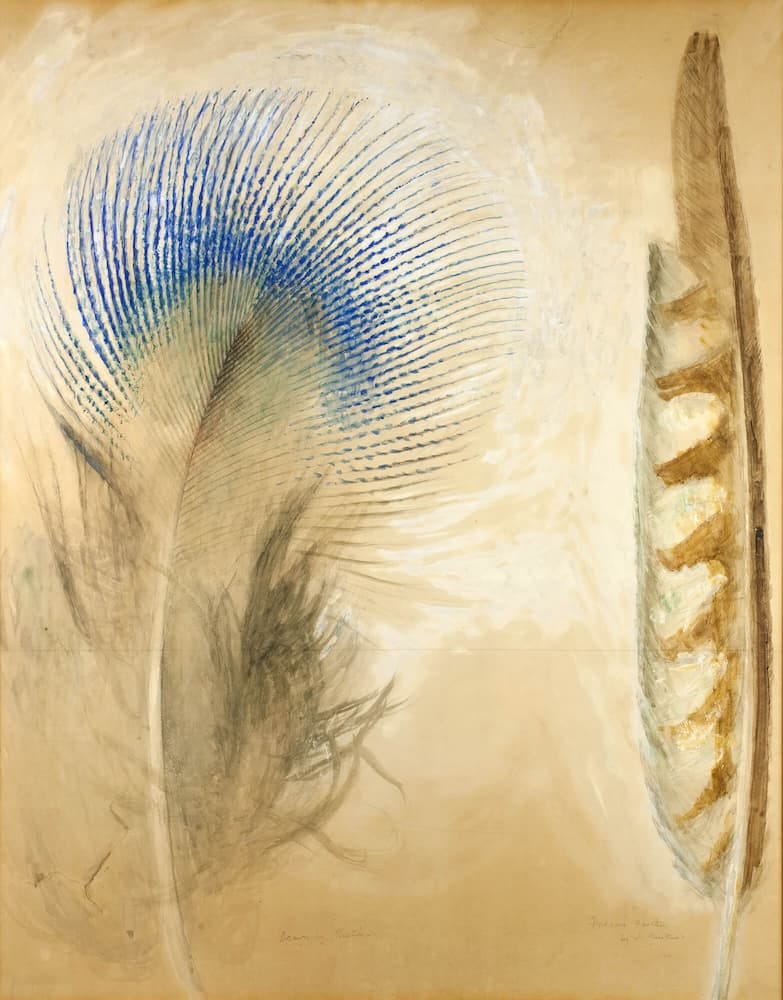

…A brave new world filled his senses with the sacramental energy of creation where every bird, tree, branch, and blossom trembled with divine immanence.”

As the biographer Paul Mariani put it, Hopkins had “a sacramental vision of the world.”

In a wonderful podcast episode devoted to “As Kingfishers Catch Fire,” Andy Patton says that if we can understand what Hopkins is doing in this poem, it can be a key to unlocking his other poems.

(Many of the following insights I owe to Patton, and I highly recommend his Rabbit Room podcast series on the poet.)

Hopkins was obsessed with the musicality of poetry. He wrote his poems to be read aloud. In the first stanza, Hopkins gives us six images in quick succession: a kingfisher, a dragonfly, a stone, a well, a string, a bell. The alliteration and assonance together form a kind of onomatopoeia:

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell's

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

As we say the words aloud, we can almost hear the stone ringing as it falls into a well or hear the pluck of a taut string.

Hopkins holds up these things as examples of what he’s about to say next:

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.

In other words, each created thing expresses itself, its very essence, simply by doing the things it was made to do.

Here we come to two concepts which Hopkins explored frequently in his journals and poetry: inscape and instress.

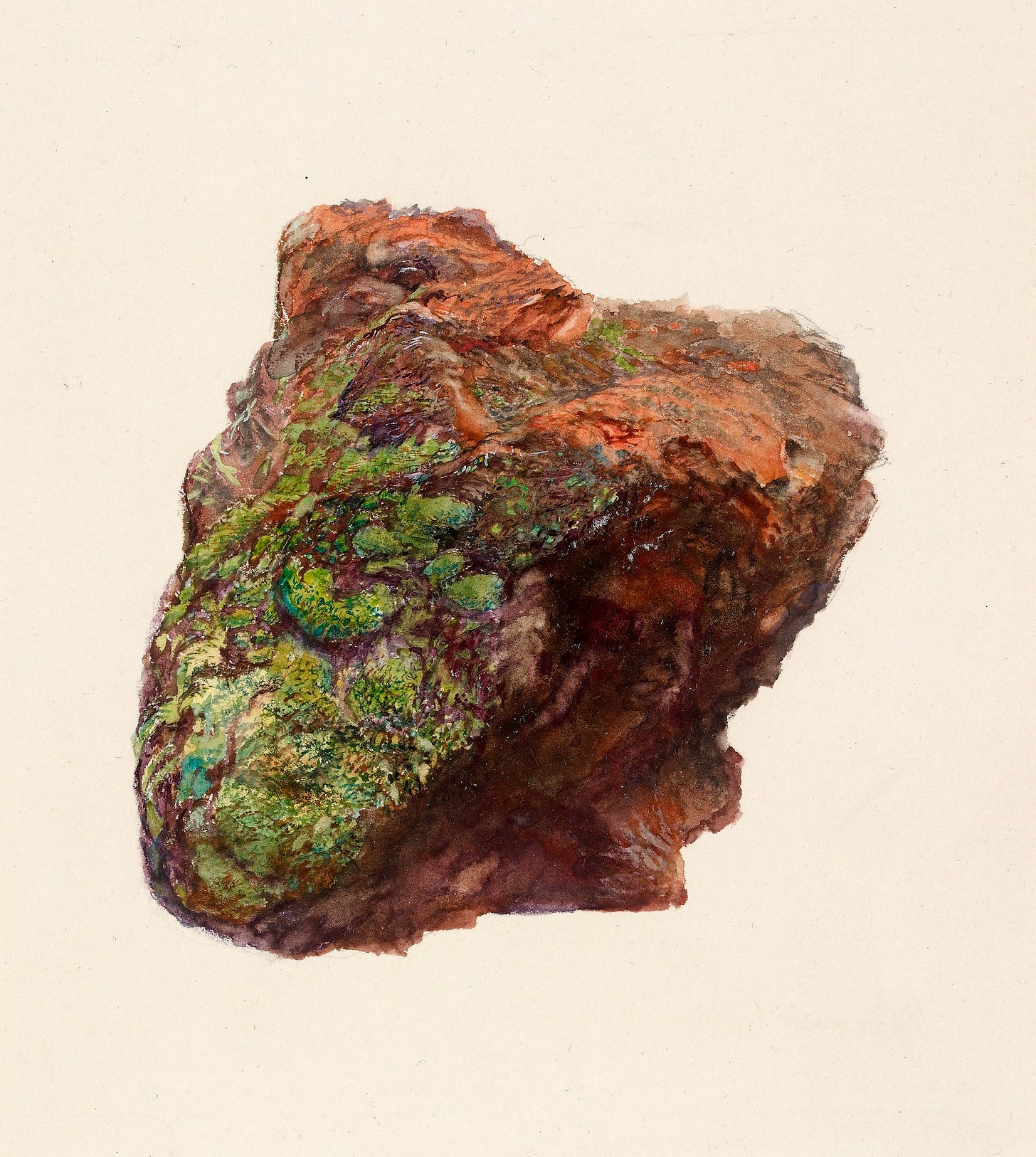

“Inscape, for Hopkins, is the charged essence, the absolute singularity that gives each created thing its being; instress is both the energy that holds the inscape together and the process by which this inscape is perceived by an observer. We instress the inscape of a tulip, Hopkins would say, when we appreciate the particular delicacy of its petals, when we are enraptured by its specific, inimitable shade of pink.”1

As Patton says, we might think of inscape as a thing’s thingness or its interior landscape. It’s what gives each thing it’s particular beauty. And because Hopkins believed in a God who created the world, he believed strongly that all things bore the mark of their Creator—simply by doing that which they were created for.

As he wrote in his journal:

“All things therefore are charged with love, are charged with God and if we knew how to touch them give off sparks and take fire, yield drops and flow, ring and tell of him.”

In the second stanza, Hopkins shifts his attention from things in nature to man himself and, most importantly, that being indoors each one dwells.

I say móre: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: thát keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God's eye what in God's eye he is —

Chríst — for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men's faces.

According to Patton:

“[Hopkins] seems to pivot to the ultimate thing he finds inside of everything: God. Theologians have spilled oceans of ink parsing out what it means that humanity is made in the image of God. For my money, Hopkins accomplishes more in the last six lines of this poem than any of them. He says that God has left his imprint on humanity, his image. And so his people are also images of him—icons, vectors of his presence and way in the world. So, that being indoors each one dwells is ultimately Christ. To Hopkins, our graces, our just acts, all our goings—those ways we selve ourselves—can become ways “Christ plays… lovely in limbs, lovely in his eyes not his…to the Father, through the features of men’s faces.”

Let’s go back to that wonderful line Hopkins wrote in his journal:

“All things therefore are charged with love, are charged with God and if we knew how to touch them give off sparks and take fire, yield drops and flow, ring and tell of him.”

To my mind, the crucial phrase is “if we knew how to touch them.” Of course, it begs the question: how do we learn how to “touch” things so that they spark, take fire, and tell of God? In other words, how do we instress the inscape of things? How can we learn to see the divine within the everyday?

Sometimes, it catches us unawares, like when we encounter a staggering beauty that brings us to tears (e.g. seeing the Grand Canyon for the first time or hearing a gorgeous piece of classical music). Other times, it’s great pain that gives us a glimpse of heaven in the everyday (see “From a Window” by Christian Wiman). But we can also learn to access the divine nature of things by cultivating the patient practice of attention.

This, in my opinion, is one of poetry’s greatest gifts. Hopkins insisted that revealing the inscape, the singular beauty within each thing, was the essence of poetry2. But it can only be accessed if we take the time and pay close attention.

Which perhaps is why, as Patton suggests, Hopkins wrote his poetry in such a unique way. His style—which many considered strange, confusing, and opaque—forces us to slow down and pay attention, so that we might instress the inscape of whatever it is he’s writing about.

Patton, again:

“And maybe that’s one reason why it didn’t bother him very much if people said [his poems] were complicated or hard to understand. The jewels weren’t meant to lay on the surface for the taking. They’re supposed to be buried, to bring the reader to a stillness that demands attention and patience. Perhaps he wanted us to go on a journey into and through the poem…”

No subject was too small for Hopkins’ poetry. In fact, it’s almost as if the smaller the thing, the better. For it was in this microscopic, razor-sharp attention to the details of things, where Hopkins found “the power of particularity,” which could “change a person forever.”3

It may be musing on the “rose-moles all in stipple” on a trout, as in his marvelous poem “Pied Beauty”:

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Or the dappled wings of a falcon as in his poem “The Windhover” (which Hopkins considered to be his greatest work):

I caught this morning morning's minion, king-

dom of daylight's dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

Whatever he beheld, Hopkins wanted to take the reader on a journey into the divine, interior landscape of his subject. As Patton says, “his poems, if we instress them too, are doorways to the inscape he saw and doorways to the God he saw there.”

I believe Hopkins’ poetry, his sacramental vision of the world, and his belief in the “the power of particularity” are potent antidotes for some of what ails us in our modern, Machine age.

Let us not forget: we live in an age of disenchantment. Our rationalistic way of thinking reduces everything to sheer materiality. Internet culture, for all its benefits, tends to flatten reality, generalize it, and de-mystify it. What’s more, our attention has become the number one commodity in the marketplace. A fundamental feature of life in the modern world is having one’s attention scattered in a hundred different directions.

We no longer know the names of trees.4 How can we, when we zoom by them on a highway at 70 miles per hour? Our pace of life (literally and metaphorically) prohibits us from the kind of habitual attentiveness Hopkins wrote about. Truly, we have forgotten Christ’s call to “consider the lilies.”

Perhaps Hopkins’ poetry, like all great art, can re-awaken us to the hidden, divine landscapes within the things of this world, and the Maker behind it all who is Beauty itself. As Hopkins writes in “Pied Beauty”:

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

If you found this dispatch encouraging, delightful, or helpful in any way, please like and share it! It helps more people discover this publication.

How does this Hopkins poem strike you? What do you make of his concepts, instress and inscape? Have you ever experienced the power of particularity? How do you practice it? Leave a comment below and let me know!

Post Script with Special Recording

The first time I read “As Kingfishers Catch Fire,” it gave me the chills. The first line, in particular, stopped me in my tracks. It is, in my mind, one of the best first lines of poetry ever written.

The beauty of the language in this poem is astounding. Even before I fully understood its meaning, it had a profound effect on me. I knew immediately that I wanted to memorize it, which I did over a week or so.

Here is a recording of me reading the poem while on a walk in a park.

Inscape, Instress & Distress by Anthony Domestico, Commonweal Magazine

Glenn Everett, Hopkins on "Inscape" and "Instress"

Dick Sullivan, Hopkins and the Spiritual

Or, perhaps more importantly, the names of our neighbors.

I missed this earlier in the month so I’m glad you’ve reshared! This is brilliant. I was unfamiliar with the concepts of instress and inscape but find them absolutely fascinating and incredibly helpful and powerful. Going to be revisiting this more!