Make badly and suffer gladly

On recovering our creative calling, being an amateur, and Mako Fujimura's 'Theology of Making'

“All children are artists. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.”

-Pablo Picasso

i.

A few years ago, my wife started doing arts and crafts projects with our son. He was young, maybe 3ish. She would bring out a few brushes, a palette, some watercolors, and let him go for it.

When I saw some of the paintings he did, I was floored. Don’t get me wrong—these were no Sistine Chapel frescoes. They were utterly typical for a child his age. But all the same, I was struck by the beauty of the paintings. The lack of self consciousness. The freedom. The playful joy.

Eventually, a thought crossed my mind: Why can’t I do that?

ii.

A lamentable fact of modern life is that many of us have forgotten how to create. We no longer paint paintings, sketch trees, build tables, write poems, play piano, sing songs, write stories, bake bread, or perform plays. The truth is, we do not create because we are too busy consuming. Streaming platforms like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon churn out hundreds of new shows and movies every year. Podcasts have exploded. 2.6 million videos get uploaded to YouTube each day. Social media apps are literally designed to keep us staring at our screens as long as possible. We are virtually always listening, scrolling, or watching something on a screen. We are, quite literally, amusing ourselves to death.1

In this sad exchange, we have forgotten something core to who we are and how we were designed: we were made to make. In Makoto Fujimura’s extraordinary book, Art and Faith: A Theology of Making, he writes:

“To be human is to be creative…Whether we are plumbers, garbage collectors, taxi drivers, or CEOs, we are called by the Great Artist to co-create. The Artist calls us ‘little-a’ artists to co-create, to share in the ‘heavenly breaking in’ to the broken earth.”

God is the ultimate Creator. Part of what it means to be made in his image is to share in his creative nature. This kind of generativity isn’t reserved for a handful of artisans—it’s in all of us. “The characteristic common to God and man is apparently…the desire and ability to make things,” observed the writer Dorothy Sayers.

But if we are to recover our calling as makers, as “little-a” artists, we must first make the decision to live differently. To make different choices. To consume less and create more. As Mako writes, “When we fail to stop making, we become enslaved to market culture as mere consumers.”

The magnetism of the Machine is strong. Our smartphones in particular exhibit a kind of gravitational pull to them. It will take intentionality, grace, and creativity to consistently live a life where we make more than we consume.

But like any corrosive habit we’re looking to kick, we cannot simply stop “cold turkey.” We have neither the strength nor the will. We need, to borrow a phrase from Thomas Chalmers, “the expulsive power of a new affection.” In other words, we need to experience the goodness and joy of making so as to render the “screened” life powerless. If we want to give up junk food, yes, we should probably start by removing it from our pantries. But we should ALSO make it a habit to eat healthy food that tastes so good the junk pales in comparison.

I believe if we can recover this kind of slow, embodied, creative life, we can restore a lost piece of our vitality, joy, and wholeness. Not only that, we may stumble upon a deeper experience of the Divine. Mako, again:

“I have come to believe that unless we are making something, we cannot know the depth of God’s being and God’s grace permeating our lives and God’s creation…the act of Making can lead us to coming to know THE Creator personally…”

In the West, we tend to think of knowledge as purely intellectual, a set of propositions. But we forget about somatic knowledge. There is a kind of knowing we can only experience through our bodies. As Mako illustrates in the book, it is one thing to read about making an omelette. It is another thing entirely to actually cook and eat an omelette—to hear the butter sizzling in the pan, to crack the eggs, to taste the delicious, finished dish. If God is fundamentally a Creator, and if we are truly made in the imago Dei, then a crucial part of knowing him is creating things ourselves.

iii.

Another major reason why we’ve lost our ability to make is this: We’re bad at being bad at things. We hate being amateurs. If we can’t be Michaelangelo, Shakespeare, or Bob Dylan, what’s the point of taking up the brush, the pen, or the guitar?

I think our allergy to amateurism is in some small part due to the self-improvement culture we live in. We are incredibly perfectionistic. If we can’t be truly “Great” at something, we would rather not do it at all. The thought of taking up a new hobby as an adult and suffering through the beginner phase is anathema to us. Why subject yourself to the humiliation of being terrible at something?

This kind of thinking is, of course, deeply reductionistic and utilitarian. If we were made to be makers, then cultivating a habit of creating can only do good things for our bodies, our souls, and those around us. What kind of joy might our simple paintings, poems, and songs bring to those we love most, just like my son’s paintings brought to me? What might the consistent habit of writing a poem or sketching a tree do for our souls, even if no one ever laid eyes on our work?

In the television series Mozart in the Jungle, Gael García Bernal plays Rodrigo De Souza, the new conductor of the New York Symphony. In one memorable scene, he hears Gloria Windsor, the symphony president, singing in her apartment. Amazed by her voice, Rodrigo tells her she should be performing in front of a large audience.

“I’m just an amateur,” she demurs. Rodrigo replies, “You say amateur as if it was a dirty word. ‘Amateur’ comes from the Latin word ‘amare’, which means to love. To do things for the love of it.”

We need to recover making things simply for the love of it.

iv.

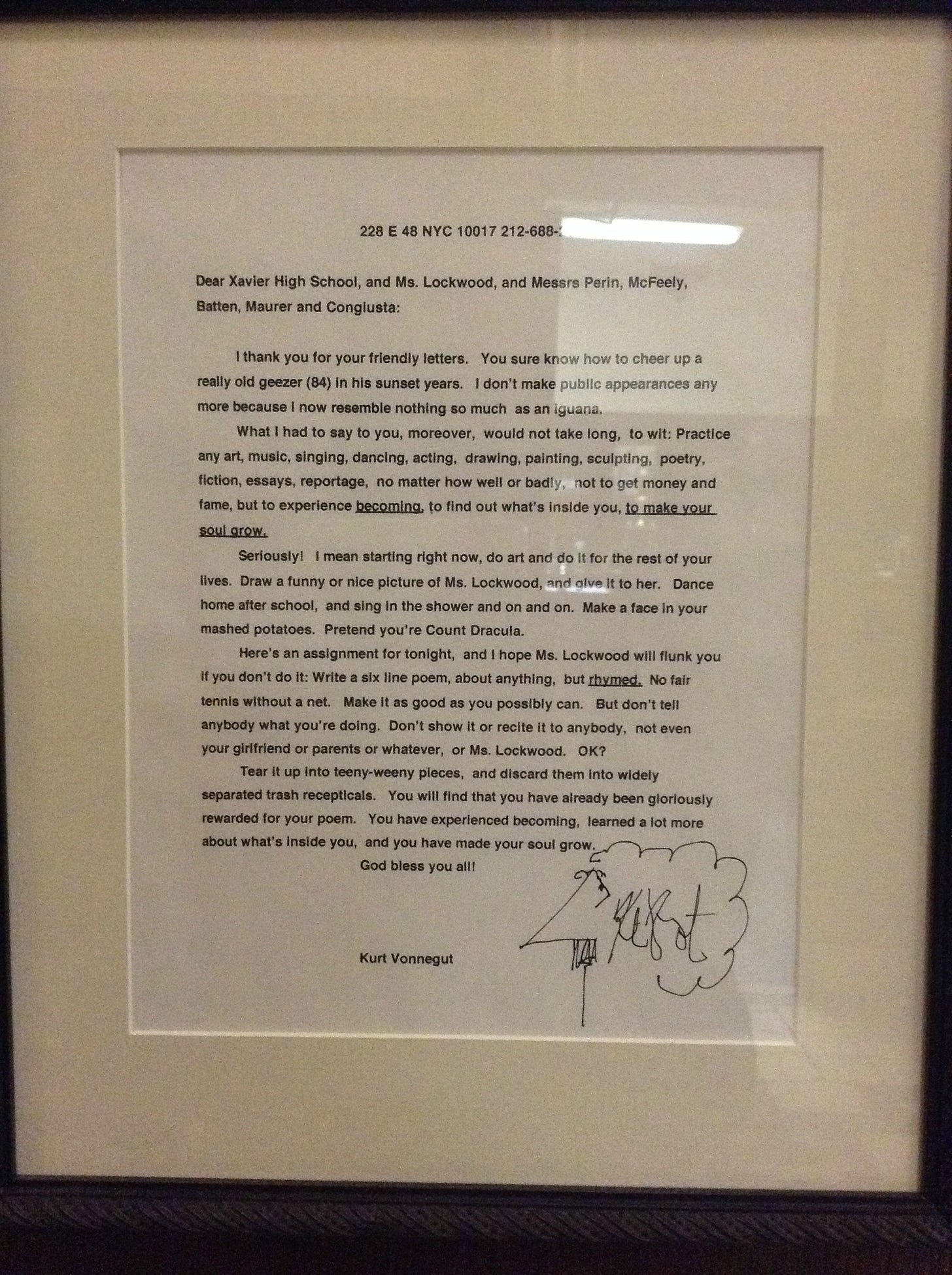

In 2006, a high school English teacher asked students to write a famous author and ask his or her advice. Kurt Vonnegut, the famed author of Slaughterhouse Five, was the only one to respond. The entire letter is hilarious (see the picture below), but the crux of Vonnegut’s advice is:

“Practice any art, music, singing, dancing, acting, drawing, painting, sculpting, poetry, fiction, essays, reportage, no matter how well or badly, not to get money and fame, but to experience becoming, to find out what’s inside you, to make your soul grow. Seriously! I mean starting right now. Do art and do it for the rest of your lives.”

Vonnegut goes on to give the students “an assignment”: write a six-line poem about anything, but it must be rhymed.2 “Make it as good as you possibly can. But don’t tell anybody what you’re doing. Don’t show it or recite it to anyone…”

Then, “Tear it up into teeny-weeny pieces and discard them into widely separated trash receptacles. You will find that you have already been gloriously rewarded for your poem. You have experienced becoming, learned a lot more about what’s inside you, and you have made your soul grow.”

The thing that stands out about Vonneguts advice is his adamant belief in the intrinsic value of making art—even if we do it badly. To him, the quality of the finished product (at least in the beginning) is irrelevant. It’s in the doing where we become, where our souls grow.

To be clear, I am not saying we should celebrate truly bad art or lower our creative standards. I don’t think Vonnegut is saying that either. It is a good thing to aspire to excellence in our craft (whatever it may be). In many ways, we’re called to pursue it.3 But unreasonably high expectations can be a barrier to entry to any creative pursuit. In our über-competitive, instant-gratification culture, we are quick to give up on something if we are not immediately proficient at it. (Or if we sense we’ll never be truly “Great” at it.) But just because you probably will never sell out Madison Square Garden doesn’t mean you shouldn’t learn to play guitar.

Will it be hard? Yes, especially in the beginning. Even the most basic command of an instrument requires discipline, patience, practice, and perseverance. Herein lies another point that explains our atrophied making skills: we would rather choose easy over hard. In the age of the Machine, easy or easier is almost always the central promise of a new piece of technology. Why work so hard to learn to play guitar when I can play any song I want through a streaming service on my bluetooth speaker?

Learning to make again will be challenging. But we know in our bones that a life of making is far more beautiful and fruitful than a life of consuming. And besides, any artist worth their salt will tell you—to master a craft, you must start at the bottom. The path to greatness begins in the land of amateur.

v.

When a child is creating, they do so with a striking lack of self-conciousness. As I observed my own son delight in the materials, the colors, and the sheer act of making, it rekindled a longing within me. Something that had been lost. I wanted to experience the joy of making again.

So about a year ago, I took up sketching. Which is funny, because I have never really sketched. Even when I was a kid, I didn’t do it much (partly because I felt I wasn’t very good at it).

Personally, I have found the experience of being a total novice to be utterly thrilling. I try to approach it like a child, with no expectation or self-criticism—just being in the moment, enjoying the materials, and embracing the process. As adults, we rarely try something new. Anything that falls firmly outside our sphere of competence feels a bit terrifying. But I have found a certain vitality in it—so much so that I have started experimenting with ink and watercolors. The pieces I’m creating are neither great nor good. But I really like doing them. They delight my kids. And it sure beats the hell out of watching Netflix every night.

Like all art forms, drawing and painting are challenging. I make tons of mistakes. I would not say either comes “naturally” to me. It is thoroughly humbling. But despite the difficulty, or perhaps because of it, I have discovered a deep joy in the practice, especially in the materials themselves: the pen, the nib, the ink, the paper, the brush, the water, the paint. In a highly digital world, where so much of our lives is mediated through screens, working with raw, tangible materials is remarkably restorative. And the more I make, the more I want to make. I feel less and less drawn to my phone and more and more to my little art station.

vi.

In many ways, this Substack was born out of desire to create again. To rediscover my love of writing and learn the craft anew. Before launching it, I hadn’t written anything outside of work for over four years. As I got back into the habit of writing long-form essays, I felt insanely rusty—like a baby deer learning to walk on its legs for the first time. On ice. In many ways, it feels like I’m learning to write all over again. But I couldn’t be happier to slog away at it. It’s been such a gift.

Certainly, I desire to paint a good painting, pen a good poem, and write a good essay. Perhaps one day, decades from now, I shall. But for now, I am content to create for much simpler reasons. For the benefit of my body and soul, yes. But above all, for love. For the love of my Maker, my family, and my friends.

The same is true of the God whose image we bear. As Mako writes:

“So why did God create? Our view of the creative process and the role of art hinges on how we answer this question. God created out of love. God created because it is in God’s nature to make and create.”

Which, to this father of three, brings to mind a memorable line from that great lyricist, Daniel Tiger:

Making something

is one way

to say

I love you.

Thanks for reading. If you found this essay interesting or encouraging in any way, please show your appreciation with a comment, like, restack, or share. It helps spread the word to more people!

What do you think? What creative practices do you engage in and how have they “enlarged your soul” and blessed your friends, family, and neighbors? How might consuming less and making more lead us to greater flourishing? Let me know in the comments below!

To borrow the title of Neil Postman’s book, ‘Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business’

“No fair tennis without a net.”

“Whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord, not for human masters, since you know that you will receive an inheritance from the Lord as a reward. It is the Lord Christ you are serving.” Colossians 3:23-24 (NIV)

This is beautiful. I love it (and that classy reply by KV). Now I’m going to close this device, get off the sofa and go off and play a few tunes - hopefully reasonably well, but if not, no matter.

My inner child feels very seen by this essay. So beautiful!